The songs and morphology of the seven periodical cicada species are described on pages linked below. General behavior is described here.

The genus Magicicada contains the periodical cicadas, known for their 17- or 13-year synchronized life cycles and dense choruses. These cicadas have striking black bodies, red eyes, and red wing veins. Males and females join dense aggregations, or leks, where the males search for the stationary females using short flights and calls.

Some cicadas have white or blue eyes, and some lack red pigmentation on their wing veins. These color variations are natural and are presumed to be caused by mutations or rare alleles. Individuals of all periodical cicada species can be found exhibiting these variations.

Species Groups

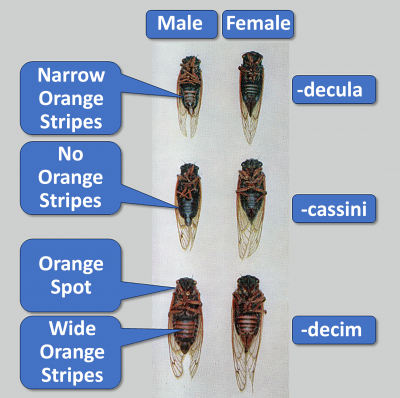

There are three species groups of periodical cicadas, designated as -decula, -cassini, and -decim:

The species groups are distinctive in appearance and behavior. Each of the species groups contains multiple species, and each species group appears to be monophyletic- that is, all of the -decula species share a common ancestor that was a -decula cicada, all of the -cassini species share a common ancestor that was a -cassini cicada, and all of the -decim species share a common ancestor that was a -decim cicada.

Life Cycles

Periodical cicadas have life cycles of either 13 or 17 years. The life cycles are not necessarily monophyletic; that is, not all 13-year cicadas necessarily have a 13-year ancestor, and not all 17-year cicadas necessarily have a 17-year ancestor. Life cycle length is a homoplasious character in Magicicada.

Species

Magicicada species are as follows:

| Species group | 13 | 17 |

|---|---|---|

| -decim | M. tredecim | M. septendecim |

| -cassini | M. tredecassini | M. cassini |

| -decula | M. tredecula | M. septendecula |

Three 17-year cicada species are described, and for each, there is at least one morphologically and behaviorally similar species with a 13-year life cycle. Thus, the closest relative of each Magicicada species appears to be a counterpart with the alternative life cycle (hence, life cycles must be homoplasious). Some species pairs can be distinguished only by life cycle and geographic distribution. Some biologists have argued that the life cycle difference alone is not enough to justify species status. More information on the nature of the boundary between 13- and 17-year populations and the extent of hybridization between them would help to resolve this question, but for now there is no evidence that the distinctiveness of the life-cycle-forms is decreasing. For this reason and for practical purposes, most writers have adopted the taxonomy that recognizes the life cycle siblings as distinct species.

Which species are found in which broods?

Most of the broods contain all of the 13- or 17-year species, with a few exceptions. Brood VI lacks Magicicada cassinii, Brood VII contains only Magicicada septendecim (which tends to be found alone along the northern edge of the 17-year range), and 13-year Brood XXII lacks Magicicada neotredecim. The four 13-year species are all found together in only a limited portion of the 13-year range (see below).

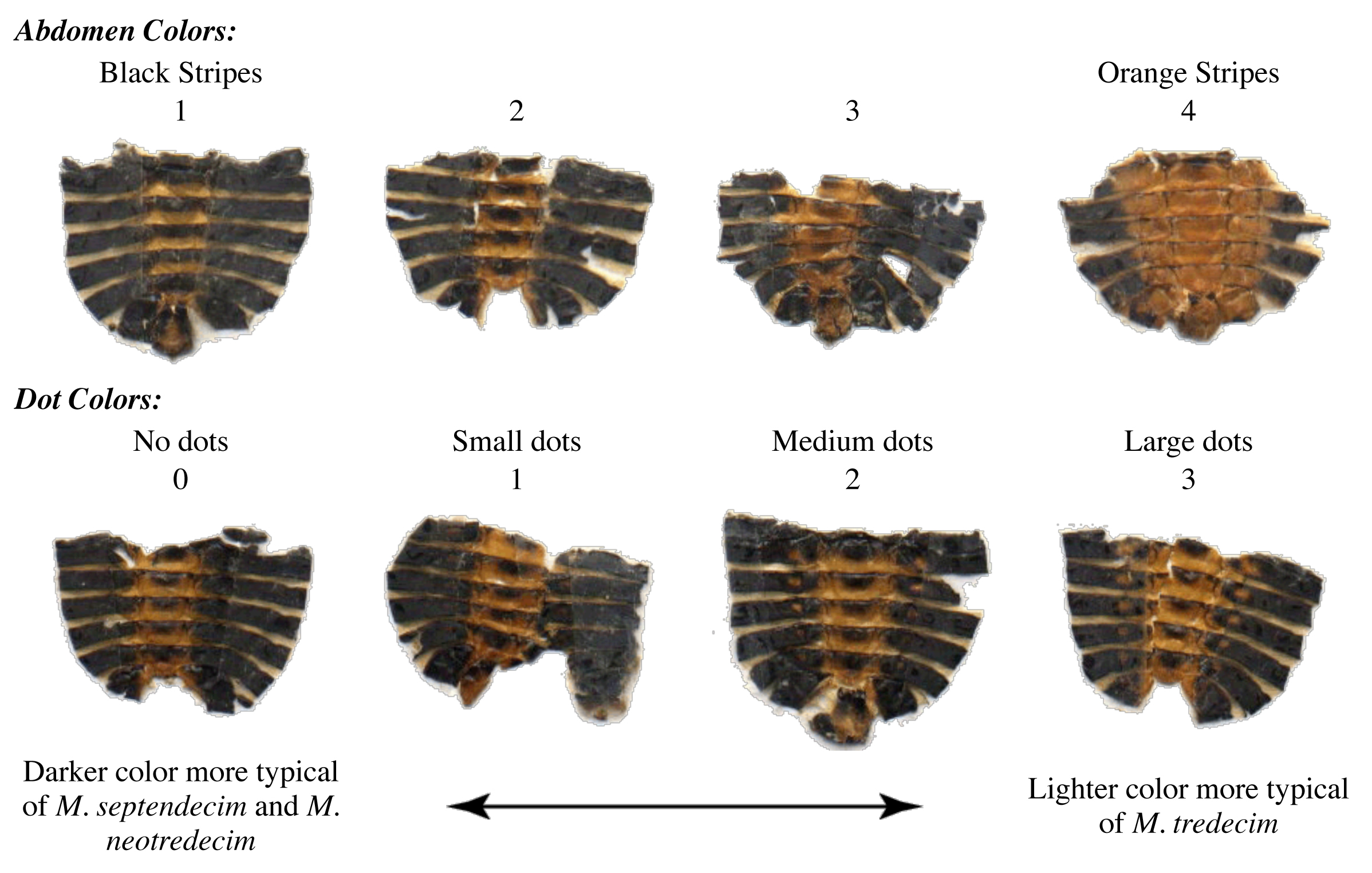

Color variation in the -decim species

The -decim species (M. septendecim, M. neotredecim, and M. tredecim) have orange abdominal stripes. However, there is significant variation in the appearance of the stripes; M. septendecim and M. neotredecim (mitochondrial lineage “A”) tend to be darker in appearance, while M. tredecim (mitochondrial lineage “B”) tend to be lighter.

Reproductive Character Displacement in the -decim species

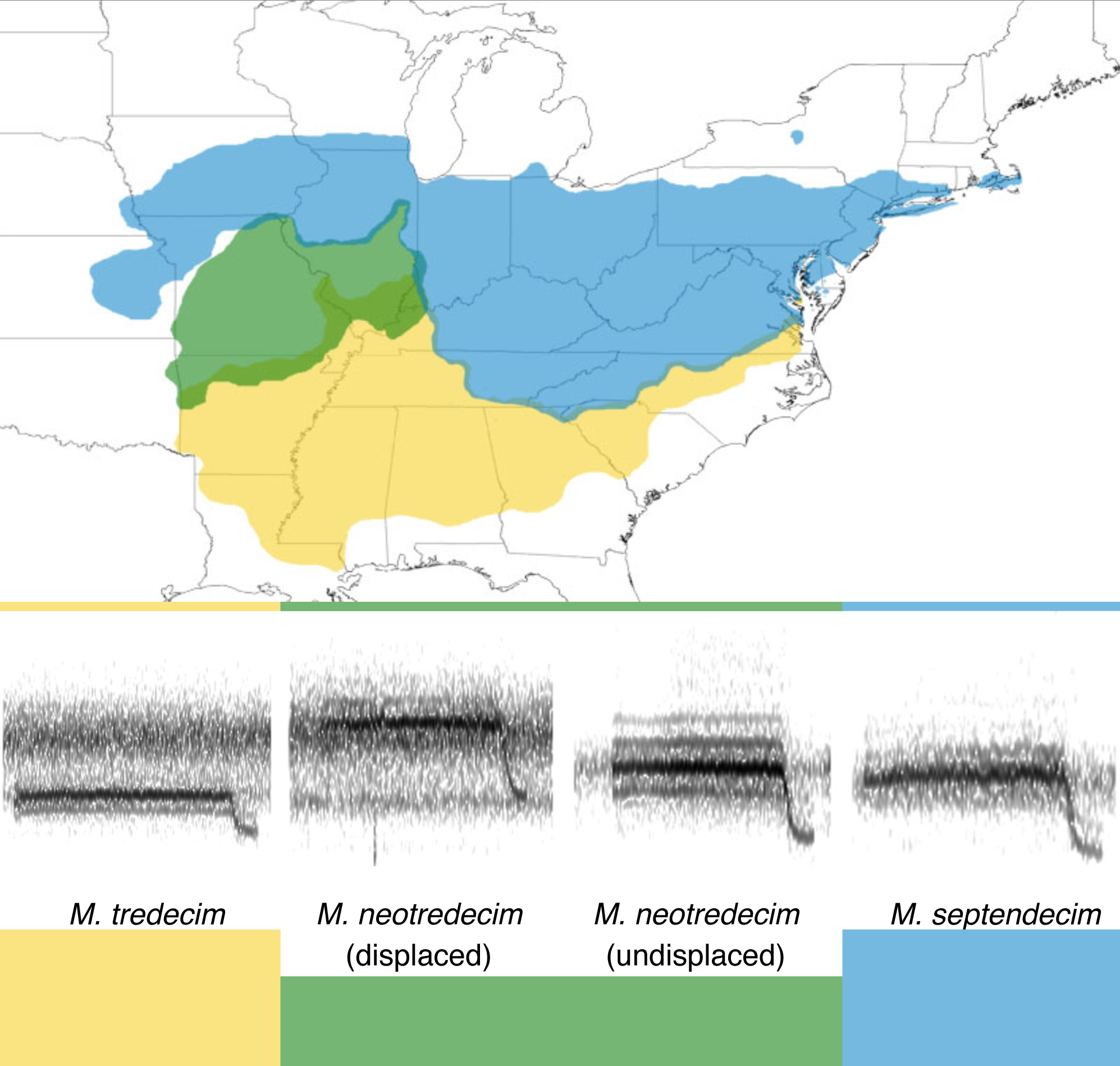

The two 13-year -decim species have a special geographic relationship — they are not sympatric (living together) across the entire 13-year range. Magicicada neotredecim inhabits the midwestern part of the 13-year range, while M. tredecim inhabits the southern and southeastern part. The two species overlap only along a narrow region in northern Arkansas, western Kentucky, and southern Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana. By comparison, the three 17-year species are found together from Connecticut to Kansas, and the remaining 13-year species together inhabit most 13-year populations. Where Magicicada neotredecim and M. tredecim overlap, male calling songs (and female song preferences) of these species have evolved to become more distinct. In this overlap zone, Magicicada neotredecim songs are much higher-pitched, while M. tredecim songs are slightly lower-pitched. This pattern of reproductive character displacement suggests that the songs have evolved to reduce wasteful sexual interactions between the species.