General Periodical Cicada Information

Periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) are among the most unusual of insects, with long life cycles, infrequent, periodic and synchronized mass emergences, striking appearance, and noisy behaviors. No other insects are known with this combination of attributes.

Periodical cicadas are found only in eastern North America. There are seven species — four with 13-year life cycles and three with 17-year cycles, all of which originated from a common ancestor approximately 3.9Mya (Simon et al. 2022). The current taxonomic classification of Magicicada is:

| Phylum | Arthropoda |

| Class | Insecta |

| Order | Hemiptera |

| Suborder | Auchenorrhyncha |

| Family | Cicadidae |

| Subfamily | Cicadettinae |

| Tribe | Lamotialnini |

The earliest known fossil specimens of the Lamotialnini date to 8.5-8.0 Mya (Late Miocene) in present-day France (Jiang et al. 2025).

The three 17-year Magicicada species are generally northern in distribution, while the 13-year species are generally southern and midwestern. The periodical cicadas can be divided into three species groups (-decim, -cassini, and -decula) with slight ecological differences. Magicicada are so synchronized developmentally that they are nearly absent as adults in the 12 or 16 years between emergences. When they do emerge after their long juvenile periods, they do so in huge numbers, forming much denser aggregations than those achieved by most other cicadas. Periodical cicada emergences in different regions are not synchronized, and different populations comprise the 15 largely parapatric periodical cicada “Broods,” or year-classes.

Many people know periodical cicadas by the name “17-year locusts” or “13-year locusts”, but they are not true locusts, which are a type of grasshopper. Their uniqueness has given them a special appeal and cultural status. Members of the Onondaga Nation near Syracuse NY maintain the oral tradition of being rescued from famine by periodical cicadas. Early European colonists viewed periodical cicadas with a mixture of religious apprehension and loathing. Modern Americans maintain numerous websites to assist in planning weddings, graduations, and other outdoor activities around Magicicada emergences.

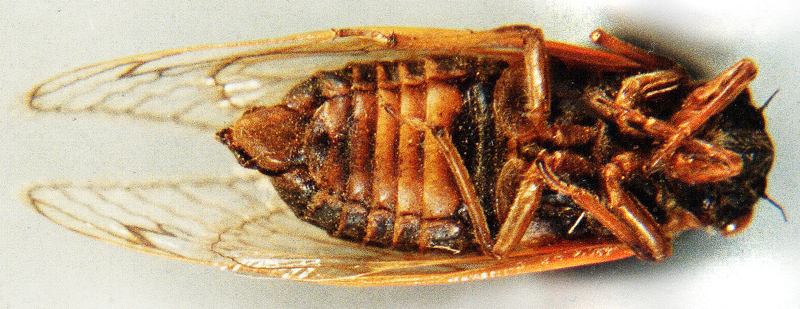

Magicicada adults have black bodies and striking red eyes and orange wing veins, with a black “W” near the tips of the forewings. Most emerge in May and June. Some of the annual cicada species are sometimes mistaken for the periodical cicadas, especially those in the genera Diceroprocta and Okanagana; these other species emerge somewhat later in the year but may overlap with Magicicada. The Okanagana species are the most potentially confusing because some have similar black-and-orange coloration. Other Common North American non-periodical cicadas include the large, greenish “dog-day” cicadas (genus Neotibicen) found throughout the U.S. in the summer. Non-periodical cicadas are often called “annual cicadas” (even though they typically have multiple-year life cycles) because in a given location adults emerge every year. The best way to identify cicada species is by the sounds that they make, because cicada songs are nearly always species-specific.

Cicadas do not possess special defensive mechanisms — they do not sting or bite. The ovipositor is used only for laying eggs and the mouthparts are used only for feeding on twigs; thus, periodical cicadas can hurt you only if they mistake you for a tree branch! When approached, a cicada will simply fly away. If handled, both males and females struggle to fly, and males make a loud defensive buzzing sound that may startle but is otherwise harmless. Cicadas are not poisonous or known to transmit disease.

What to expect during an emergence

Cicada juveniles are called “nymphs” and live underground, sucking root fluids for food. Periodical cicadas spend five juvenile stages in their underground burrows, and during their 13 or 17 years underground they grow from approximately the size of a small ant to nearly the size of an adult.

Periodical cicada nymphs live underground for 13 or 17 years, keeping track of seasonal cycles (Karban et al. 2000) through some as-yet unknown mechanism. Available evidence suggests that in the Fall before the nymphs emerge, their eyes become red. In the spring of their 13th or 17th year, a few weeks before emerging, the nymphs construct exit tunnels to the surface, with exit holes roughly 1/2 inch in diameter. Sometimes cicadas miscount and emerge unexpectedly early or late and they are called “stragglers”.

Sometimes, nymphs construct mud “turrets” surrounding their holes, though the context in which cicadas construct turrets and the functional significance of the turrets remains unknown. The characteristic black thoracic patches seem to appear just before emergence; we have never dug up nymphs that have them, while all emerging nymphs we have seen have them.

Locally, periodical cicada emergences occur when soil temperatures at a depth of 7-8 inches reach approximately 64°F (Heath 1968). Because emergence is temperature-dependent, periodical cicadas tend to emerge earlier in southern and lower-elevation locations. For example, cicadas in South Carolina often begin to emerge in late April, while those in southern Michigan do not appear until June. The best way to predict the time of emergence for your area is to check records from the prior emergence in that location, by asking longtime residents or by searching local newspaper archives. Emerging nymphs leave their burrows after sunset (usually), locate a suitable spot on nearby vegetation, and complete their final molt to adulthood.

Shortly after ecdysis (molting) the new adults appear mostly white, but they darken quickly as the exoskeleton hardens. The cues that determine the particular night on which the nymphs emerge and molt are not well understood, but soil temperature probably plays an important role. Sometimes a large proportion of the population emerges in one night. Newly-emerged cicadas spend roughly four to six days as “teneral” adults before they harden completely (possibly longer in cool weather); they do not begin adult behavior until this period of maturation is complete.

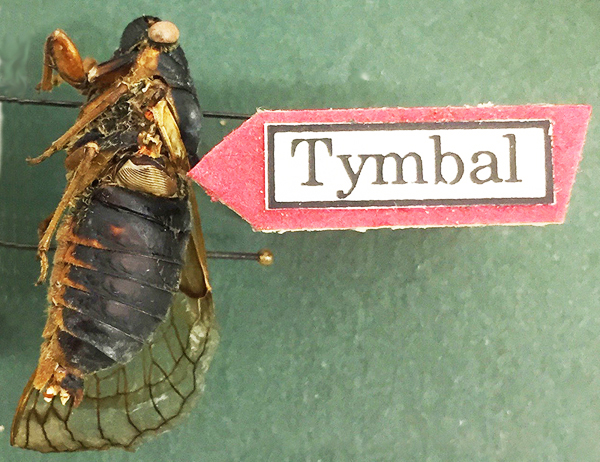

After their short teneral period, males begin producing species-specific calling songs and form aggregations (choruses) that are sexually attractive to females. Males in these choruses alternate bouts of singing with short flights until they locate receptive females. Click here to learn more about their behavior.

Contrary to popular belief, adults do feed by sucking plant fluids; adult cicadas will die if not provided with living woody vegetation on which to feed. Adult Magicicada feed from a wide variety of deciduous plants and shrubs, but usually not from grasses.

Mated females excavate a series of Y-shaped eggnests in living twigs and lay up to twenty eggs in each nest. A female may lay as many as 600 eggs.

After six to ten weeks, the eggs hatch and the new first-instar nymphs drop from the trees, burrow underground, locate a suitable rootlet for feeding, and begin their long 13- or 17-year development.

By the time that the nymphs hatch, the adults have died.

Population Densities

Periodical cicadas achieve astounding population densities, as high as 1.5 million per acre. Densities of tens to hundreds of thousands per acre are more common, but even this is far beyond the natural abundance of most other cicada species.

It turns out that it is extremely hard to estimate the population sizes of periodical cicadas, for any number of reasons. The oft-quoted figure of densities that can exceed a million per acre comes from a census taken during the 1956 emergence of Brood XIII in Raccoon Grove, IL (Dybas and Davis 1962).

If we accept a rough estimate of one million cicadas per acre… should that be surprising? How many ants are there per acre? How many mayflies? How many fruit flies? Insects often come in large numbers. What’s special about Magicicada is not the large numbers per se, but the periodicity– the predictable, synchronous emergence of large numbers of adults and their near-total absence in the years between (see the “straggler” page for more information).

The state of Delaware is roughly 1.5 million acres in size. If we accept an estimate of a million cicadas per acre and if the total combined area of a periodical cicada emergence is roughly the size of Delaware, then more than a trillion will be present– but not all in the same place at the same time.

Apparently because of their long life cycles and synchronous emergences, periodical cicadas escape natural population control by predators, even though everything from birds to spiders to snakes to dogs eats them opportunistically when they do appear. Magicicada population densities are so high that predators apparently eat their fill without significantly reducing the population (a phenomenon called “predator satiation”), and the predator populations cannot build up in response because the cicadas are available as food above ground only once every 13 or 17 years.

Magicicada do not have any specialized predators, though many different kinds of animals will eat them. Individual periodical cicadas are slower, less flighty, and easier to capture than other cicadas, probably because the safety afforded by their great numbers means that the risks of predation for an individual are low. Explaining the evolution of such an unusual life strategy is one of the most difficult problems for biologists.

Understanding the evolution of long life cycles and periodicity

It’s easy to focus on the long life cycles (13 or 17 years) of periodical cicadas. However, the life cycles of most cicadas are unknown, although it appears that the majority have multi-year life cycles. Thus, long life cycles per se may not be that unusual. It’s also easy to focus on the fact that both periodical cicada life cycles are prime numbers– but then again, if the majority of cicada life cycles were to fall between one and 20 years, the interval [1…20] contains an atypically high density of prime numbers. Thus, prime numbers per se may not be all that unexpected.

What makes periodical cicadas unusual is the combination of long life cycles, mass emergences, and periodicity, such that the vast majority of individuals in a population emerge on the same schedule and after a set number of years. If we accept that there are likely over 5000 species of cicadas in the world (more are being discovered all the time), then fewer than 10 species are periodical cicadas, and of those 10, seven are the Magicicada species of eastern North America. Whatever the conditions that led to the evolution of this life history pattern, they must have been unusual indeed!

Hypotheses for the evolution of periodicity generally fall into two categories: 1) Periodicity was shaped by glacial cycles (e.g., Yoshimura 1997); 2) Periodicity was shaped by predation pressure (e.g., Lloyd and Dybas 1966b). However each of these classes of explanation seems insufficient- the majority of insect species living in temperate areas are living in places that were affected by glaciation, yet very few are periodical, and all species of insects face predator pressures, yet very few are periodical. Glaciation and/or predation are clearly not sufficient to explain the evolution of periodical cicada life histories, or periodicity would be much more common. Evidently, there was some other as-yet unknown factor involved in the evolution of these unusual insects.